Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and the Good For Her Cinematic Universe

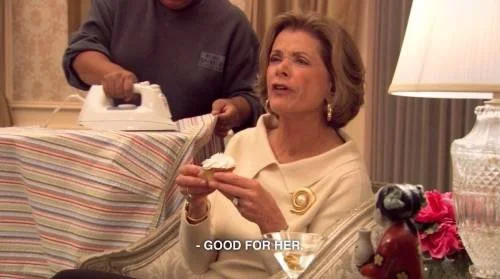

“Claiming she could take it no more, the young mother released the emergency brake, allowing her car to roll backwards into the nearby lake.”

“Good for her.”

Originally aired in 2005, the above quote from Lucille Bluth has become an internet icon. In the mid-2010s, the Lucille screenshot started circulating around Tumblr essentially any time a woman (fictional or not) did anything morally questionable. Good for her, we stan an icon. In August 2020, Twitter user @cinematogrxphy shared a photo set of the Good-For-Her cinematic universe, including Dani from Midsommar, Amy Dunne from Gone Girl, and Cecelia from The Invisible Man, amongst others. Since then, the Good-For-Her genre has snowballed, inspiring Letterboxd lists, feminist analysis and a dedicated fandom.

The typical Good-For-Her film is rooted in the horror / thriller genre where historically women have been sexualised, victimised, and tortured to no end (see the torture porn movies of the mid 00s). The Good-For-Her film will subvert the typical expectations, and have the final girl be victorious, typically getting violent revenge on the men who have hurt her. It’s easy to see why so many women gravitated towards the genre; we love seeing gaslit women break free from their abusive, patriarchal partners and set everything on fire. Women characters regaining their own autonomy with a trail of bodies behind them is frankly iconic: good for her indeed.

As much as I love female rage and all the associated catharsis and blood, let’s talk about the Good-For-Her implications of female sexuality, and rewind back to 1953’s Gentleman Prefer Blondes. Based on the 1949 musical written by Joseph Fields and Anita Loos, Gentleman Prefer Blondes is arguably an early adopter of the Good-For-Her mantra in that women get what they want in morally dubious ways. The story follows Lorelei (Marilyn Monroe) and Dorothy (Jane Russell), who get into various shenanigans due to Lorelei’s golddigging tendencies. Lorelei is a woman in the 1950s with limited prospects; she left her small town Little Rock with no education, no money, and no prospects. She works as a showgirl with Dorothy, but her ambitions are much higher than that – she’s all about financial stability. Lorelei uses her sexuality and feminine wiles to persuade rich men to give her money, and she is completely shameless about it. She essentially blackmails the millionaire owner of a diamond mine into giving her a very expensive and very shiny tiara, she scours the guest list other rich men for her friend, and she’s secured herself a rich fiancée who is more than happy to spend money on her. A woman using her looks to get ahead, despite society shaming her and calling her a slut? We have no choice but to stan. Good for her.

“Don't you know that a man being rich is like a girl being pretty? You wouldn't marry a girl just because she's pretty, but my goodness, doesn't it help?”

The film takes on an extra layer when we consider the scandals behind the two lead actresses. In 1941 Jane Russell filmed The Outlaw, the Howard Hughes Western passion project about Billy the Kid. The film didn’t get released until 1946 due to violations of the Hays Code – in particular, there was too much emphasis on Russell’s body. Hughes was so determined for the camera to focus on her breasts that he invented a specific bra for her to wear (she ended up not wearing the incredibly uncomfortable contraption designed purely to hike up her tits). For the past decade, whenever anyone was talking about Jane Russell, they were talking about her body.

Meanwhile, it’s no secret that Marilyn Monroe has been overly sexualised for her entire life and death. Gentleman Prefer Blondes was released the same year as the first edition of Playboy, where her old nude photos were used as the centrefold without her consent. This was the first time that nudes of an upcoming movie star were readily available to the general public, and naturally, she didn’t get a single dime from this.

These two objectified stars appearing together in Blondes gives them a chance to reclaim their sexuality. While they both look phenomenal every time they’re on screen, the camera doesn’t leer or gaze at them – they are sexual, but not sexualised. As a result, we believe that these women are so in control of their bodies that they can convince men to drop millions on them with a flutter of their eyelashes.

Women supporting women to leech men of their money, securing their autonomy and financial stability in a time where women had none.

Good for her.